The historyThe precursorsThe idea that the chain of the Alps, right at the point where it reaches its maximum height, could be crossed by going through a tunnel goes back a very long way. In 1787—two years before the great revolution broke out in France—an expedition organized by the Geneva naturalist Horace Bénédict de Saussure was reaching the summit of Mont Blanc, which had been conquered for the first time the year before by two mountaineers from Chamonix, doctor Michel-Gabriel Paccard and the guide Jacques Balmat. From the heights of the mountain’s 4807 metres, admiring the panorama that opened out on one side towards the plains of France and on the other side towards those of Lombardy, it crossed De Saussure’s mind—and then, in his account of the expedition, he came to write—“The day will come when they will dig under Mont Blanc a roadway suitable for vehicular traffic, and the two Valleys, the Valley of Chamonix and the Valley of Aosta, will be united”.

Between the end of the eighteenth century and the first few years of the nineteenth that idea was taken up again on several occasions: the success of the Frejus railway tunnel (started in 1857 at the wish of Camillo Cavour, in order to link the two capitals of the Savoyard kingdom, Turin and Chambéry, and finished in 1871, by which time Chambéry along with the whole of Savoy had become French, since 1860) seemed a good reason for encouraging the opening of a new transalpine railway tunnel: all the more so because in 1882 the first trains had started passing through the Swiss Gotthard tunnel, opening up an important line of communication between Italy and the centre of the European continent. Political reasons and a souring of commercial relations between Italy and France caused the idea of building a tunnel under Mont Blanc to fade, whereas that of creating a link between Italy and Switzerland through the almost 20 km of the Simplon tunnel, which was constructed between 1898 and 1906, had better fortunes. But at the beginning of the new century, at the urging of the Valle d’Aosta member of parliament Francesco Farinet, the Mont Blanc project becomes topical again. In 1907 the Turin newspaper “La Stampa” gives advance notice of the imminent construction of the tunnel, and in 1908 the French engineer Arnold Monod explains his design to a delegation of Italian and French parliamentarians, supported respectively by prime ministers Giolitti and Clémenceau, on a visit to Aosta. It was the first in-depth technical and geological study, and it would serve as a basis for the projects that followed. It offered a choice between three routes of 17.5 km, 15.1 km and 12.5 km respectively: the last mentioned one was the most warmly received, so much so that in the same year the French Minister of Public Works drew up the project for a 13 km tunnel between a point in Chamonix at a height of 1050 metres and a point in Courmayeur at a height of 1287 metres. But the climate of enthusiasm that had accompanied these events would very quickly disappear: in 1909 in France the political elections decreed the defeat of the Clémenceau government and gave rise to a period of ministerial instability and social unrest; in Italy Francesco Farinet, who had been a member of parliament for 14 years, was not re-elected and went back to being a private citizen; the Libyan war and the imminent world war would within very few years make people forget any other more peaceful project. On the other hand, objectively speaking, the Mont Blanc Tunnel no longer had a solid economic justification. Fréjus, Gotthard and Simplon were sufficient for the traffic of that time. At any rate, the time for railway tunnels had ended, and the time for road tunnels had not yet started. Towards the tunnelAfter years of silence, in 1933 Corriere della Sera publishes a long article signed by Carlo Ciucci with the title “An idea on its way to becoming reality. The Mont Blanc motorway”. What had happened? What had happened was that Antoine Bron, President of the Geneva State Council, had met the Italian senator Piero Puricelli—the engineer to whom is owed the invention and realization of the first European motorway, the Milan-Lakes motorway—and together they had contacted Engineer Monod and convinced him to turn his railway project into a road project. In 1934 Monod, who was in Bonneville, on the occasion of a conference between French, Italian and Geneva authorities, was able to explain the new project: a road tunnel of 12.620 km (so just one kilometre longer than the one that now exists) from a point above Chamonix at a height of 1220 metres (the present French entrance is at 1274 m ASL) to a point above Entrèves at a height of 1382 m (as against the 1381 m of the existing Italian entrance). It was estimated that there would be an annual traffic of 100,000 cars and 25,000 lorries, and they had even formed a detailed supposition of what the tolls might be, based on the number of passengers—from 18.60 lire or 25 francs for a four-seat car to 25 lire for one with six seats—and on the weight of goods (18.60 lire up to 1 ton, 25 lire if above that). At that moment the political relations between the Italy of Mussolini and the France of Laval were good; but shortly after (in January 1936) the Laval government fell and Léon Blum’s Popular Front took its place, and in Italy the Ethiopian war led to a reaction from the League of Nations and the application of economic sanctions (from November 1935); the Spanish Civil War, the Rome-Berlin axis and the outbreak of the Second World War would then definitively shelve the Monod project. At the end of the tragic conflict, in 1945, when the rancour and the reasons for division had not yet subsided, it was a Piedmontese engineer, Count Dino Lora Totino who understood the importance of a project capable of breaking down the natural barriers and connecting Piedmont with Western Europe. With the help of Professor Zignoli, of the Polytechnic University of Turin, various possibilities were then examined, all of them in the Valle d’Aosta: the Mont Blanc one allowed for a 12 km tunnel and a very limited section, such as would allow only 2 cars to pass in each direction of traffic or alternatively a “funicular” or shuttle system, on railway trucks. It was a very restrictive project, but that did not prevent Count Lora Totino, in 1946, from starting to excavate on the Italian side, at his own expense, and obtaining in 1947 from the Commune of Chamonix a concession over twenty hectares of land on the French side. The works had reached 60 m of full section, more than 50 m at half section and 50 m of service tunnel when, in 1947, the order arrived to suspend the activities, which no public administration had ever authorized. But the enterprising count had helped raise the problem and put before the Italian and French politicians the need to take a decision. In Italy, thanks also to the work of the Valle d’Aosta member of parliament Paolo Alfonso Farinet—grandson of that Francesco Farinet who had fought for the cause of the tunnel at the beginning of the century—it was easy to gain the support of De Gasperi and above all of the President of the Republic, Luigi Einaudi. But in France highly conflicting stances were being taken, partly because the idea of opening a road tunnel at the Fréjus was making headway: an idea that was warmly supported by the Savoy members of parliament and the “Dauphiné Libéré”, the local newspaper that had far more readers in the regions affected by this tunnel than in the regions where Mont Blanc was advantageous. At that time everybody wanted their own tunnel, convinced that opening a transalpine passage would bring important advantages to their particular route. The opponents of the Mont Blanc route also found it easy to emphasize the problem of the cost: where would the sources for financing the work be found ? The French banks hesitated and in Paris it was being said that “Mont Blanc is the tunnel for Geneva and cannot be of interest to France”. People became widely convinced that Mont Blanc was in the interest of the SNCF, which between Modane and Bardonecchia had the monopoly of goods rail transport between France and Italy, and was therefore opposed to the Fréjus road tunnel. The Mont Blanc tunnel would only have benefited the Valle d’Aosta and the port of Genoa, to the detriment of that of Marseilles. In the meantime, and with less uproar, a third transalpine tunnel was gaining support, that of the Great St Bernard: those supporting the need for it of course were the Swiss of the Valais Canton and the people of Turin, headed by FIAT, convinced that Mont Blanc would certainly be useful, but would mostly benefit Milan. It is in this context, between postponements and hesitations, that the signing in Paris on 14 March 1953 of the “Convention between Italy and France for the construction and operation of a road tunnel under Mont Blanc” is to be seen: for the moment, nothing more than a declaration of intent, signed by two ambassadors, that would take effect only after the necessary approval of their respective Parliaments. The international agreementBetween the signing of the “Convention between Italy and France” (14.03.1953) and the start of the excavation work (08.01.1959) on the Mont Blanc Tunnel just under 6 years passed. Why such a long time ? The international agreement, as we have said, had to be confirmed in specific national laws of ratification. If in Italy this took place within a reasonably quick period of time (14 July 1954 the Convention was approved by the Chamber of Deputies and on 30th of the same month it obtained the confirmation of the Senate), in France the process of approval was much longer and tormented. The day after the signing of the Convention, in 1953, the “Dauphiné Libéré” launched a series of articles with an emblematic title (“Liaisons dangereuses”) in which disastrous consequences for the French economy were foreshadowed: the opening of the Mont Blanc Tunnel would benefit Geneva and Genoa to the detriment of Marseilles and the Rhone Valley; the whole of the Alpine economy and also that of the Cote d’Azur would suffer from it, and tourists would desert the hotels of Chamonix for those of Courmayeur. Instead of spending so much money to pass vehicles from Italy into France, it would have been enough to organize car rail transport from Bardonecchia to Modane. No sooner said than done, on 15 October 1953 the first train with cars on it passed through the Fréjus tunnel: a very good argument for postponing, if not forgoing the Mont Blanc project. Between hesitations and failed attempts to bring the Convention under the scrutiny of Parliament the whole of 1954 and 1955 passed by uselessly. In September 1956, while in France people are still arguing about the advisability of setting the initiative in motion, in Turin the Italo-Swiss Convention for the construction of the Great St Bernard Tunnel is being signed and within not many months the two Parliaments approve it: so that in December 1958 the works would actually be under way. The news, together with pressure from the Italian ambassador in Paris, brought about a salutary reaction on the part of the French, and the Mont Blanc Tunnel project was finally taken to a vote in the National Assembly on 24 January 1957. But for definitive approval confirmation from the French Senate was needed and there (on 11 April 1957) its opponents still spoke about “financial madness” and “economic suicide boding ill for the interests of the Country”. Two amendments were introduced and it was necessary for there to be a second passage through the National Assembly, which finally approved the Law at 9.07 p.m. on 12 April 1957, on the eve of the recess of Parliament for the Easter holidays. Just in time, because when parliamentary work restarted the French government went into deep crisis, from which it would emerge only in 1958 with the advent of General De Gaulle and the Fifth Republic. French ratification of the international Convention now allowed the two States to give the go-ahead to setting up the Company that was to build and subsequently manage the Tunnel. In Italy, on 1st September 1957 the Società Italiana per Azioni per il Traforo del Monte Bianco was solemnly constituted in Aosta: the first President being Ambassador Francesco Jacomoni di San Savino, and the Chief Executive Engineer Giancarlo Anselmetti, from Turin. The next year, on 6 June 1958, the French Company would be established, under the presidency of Edmond Giscard d’Estaing, a member of the French Institute and father of the future President of the French Republic, Valéry Giscard d’Estaing. The constructionWhen the discussions were over and the disputes had died down, the construction works got started on 8 January 1959 on the Italian side and on 30 May on the French side. Each of the two companies carrying out the work, the Italian Società Condotte d’Acqua and the French André Borie, had the task of completing 5800 metres of tunnel. The French met with rocks of a better quality and had fewer setbacks in digging operations. On the Italian side, however, after the first 368 metres had been cut through, heavy jets of water under high pressure came out from the excavation face and forced all activities to be suspended from 20 February to 21 March. On 6 April, there was another surprise: at the 500 m point an internal landslide over a length of 100 m buried and destroyed the gantry on which were arranged the Atlas Copco hammer drills that were used to carve out the rock. This, and a later landslide of unstable material forced the miners to proceed with extreme caution, through a heavily armoured tube that was subsequently widened to half section size. Granite, a friendly kind of rock, was only found in December, when the excavation work had only just reached 1300 m; but the surprises were not over yet because decompression caused sudden “mountain knocking” sounds and the sudden detachment of blocks and sheets of rock, obliging the company to put in place systematic “nailing up” of the vault. At the end of 1960 the works were at 2.5 km from the entrance, and in 1961 more unstable and deteriorated rock, alternating with frequent gushes of water, slowed the excavation work down appreciably. In December of that year, when the 3660 m point had been reached, foreshadowed by a progressive diminution in the temperature of the rock (from the normally expected 30° it had changed to 12°), a violent gush of cold water of 1,000 litres per second, coming from under the glacier, flooded the tunnel to a depth of 40 cm: the works were suspended for about a month, until the flow of water had been reduced to 300 litres per second and could be channelled. 1962, shortly after resumption of the works, had one last tragic fatality in store for them: on 5 April three big avalanches came away from the eastern slopes of the Brenva glacier and plunged down onto the wooden huts and brick structures of the outside area of the work site, causing three deaths and thirty injuries among the workers. The mountain, not content with the many difficulties it had created for the miners, had struck them with one of its most terrible weapons.

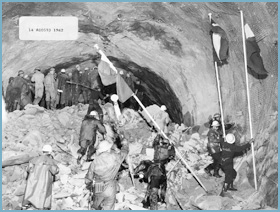

After getting through that difficult moment, the last few metres of excavation were completed between May and July. The goal of 5800 metres was achieved on 3 August 1962 and eleven days later, on 14 August, the last blast plan brought down the diaphragm that separated the Italian construction site from the French one. Almost a million cubic metres of rocky material had been extracted from the bowels of the mountain. One thousand two hundred tons of explosive had been used to supply 400,000 blasting operations. The tunnel calotte and walls had been lined with 200,000 cubic metres of concrete, and 235,000 bolts had been used to reinforce granite subject to decompression phenomena. About three years of work would still be necessary to complete the internal works, to build the carriageways, to equip the tunnel with all the technological systems needed and to fit out the two tunnel entrance apron areas. On 16 July 1965 the Mont Blanc Tunnel was solemnly inaugurated in the presence of the President of the Italian Republic, Giuseppe Saragat, and the President of the French Republic, Charles de Gaulle. Three days later, at 6 in the morning of 19 July, the new tunnel was opened to traffic. |